“When ladies have according to the French custom, set apart one morning or one evening in the week for receiving callers, it is a breach of etiquette to call at any other time, unless a short visit in the city or business that will not admit of delay are the excuses. An hour in the evening, and from ten to twenty minutes in the morning are the limits for a formal call.”

The Laws and By Laws of American Society by S. A. Frost (1869)

The act of paying calls has largely died out. We no longer have set times for visitors to come over. Some people like to have an open-door policy, others never want visitors for a variety of reasons, but no one really expects people to show up once a week for a chat – or to subsequently have to, on another day, visit all the people that visited them in return. Now we have Instagram and Facebook to learn what everyone is up to, and we can text if we want to tell a morsel of juicy gossip to a friend.

In earlier times, calling was the main way a woman could meet and make friends. Given the restrictions on leaving the home without a suitable chaperone, women were resigned to staying inside; keeping company with only their immediate family. Through calling, the world could come to a lady, even more importantly, a lady could leave her house and visit the home of another. Calling was also an excuse to dress up and show off your finest day dress. It also meant you could snoop on other peoples houses.

Everything about calling was directed towards women. While men might sometimes make calls, more often during the afternoon a man would have an office to go to, or errands to run, or a club which he frequented. Men had options and so, were not obliged to make calls. In the late 19th century, married women typically brought both her and her husband’s card with her when she called, and left them when she departed.

Calling cards have a post of their own as they are a topic all to themselves.

If you were called upon, you were expected to return a call within ten days. If you attended a party or ball at someone’s home, you had to make a “party call” within five to seven days depending on the local custom. By this method, a lady was unlikely to become very lonely. Indeed, she may have wished to be left alone.

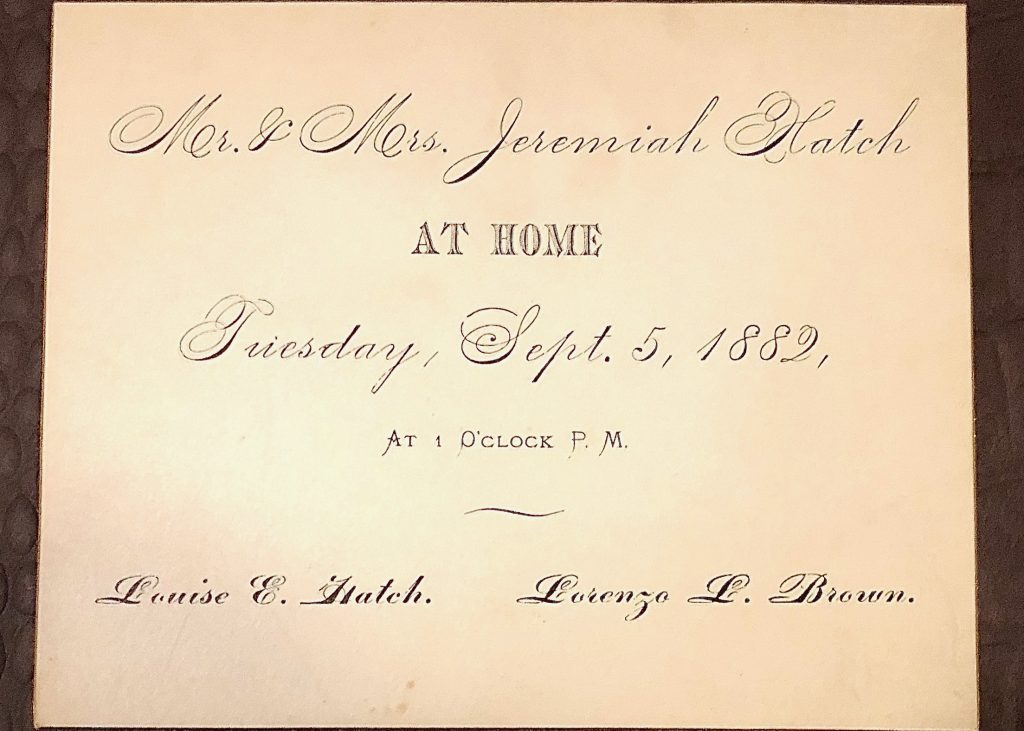

Generally, only married ladies issued at home invitations. There were exceptions to this rule, for instance, daughters of widowers might take over the social obligations of their house. Spinsters and widows could take calls, though would be seen as low down on the social circuit, unless they were particularly formidable or wealthy.

The reverse was true as well, married ladies made calls. Unmarried ladies were required to be in the company of their mother. A young woman might make calls without her mother, if she had a chaperone. A chaperone was likely a married Aunt, an older female family friend or an older brother. Society was severely limited for young single women and sadly that’s the way society liked it for a very long time.

As for how one got invited to an “At Home”, that was an ordeal of its own. If you were of high social standing, you could issue an “at home” to anyone of lower social standing, but you could not instigate a visit with someone of higher rank. If you were new to town, Letters of Introduction were a way for you to introduce yourself to someone of higher rank with the hopes that they would then include you in their social circle. Otherwise, intrepid ladies had to find women of equal or lower rank who were invited to an at home, become friends and then hope that they would put in a good word for you. Sometimes, invitations would be instigated by husbands. A man might have his wife include a colleagues’ wife in an at-home because of their work relationship.

Less so in America, but common in Britain, there was adherence to the “first call”, a woman of higher social standing could call upon a woman of lower rank, thus beginning the back-and-forth of at-home calls. In this scenario, a woman of lower rank had to wait patiently for someone to deign to visit her.

So, your acquaintance has a day for receiving callers and you were given a verbal invitation to stop by, but there is not a set time for you to go. How did the caller know when to appear? Well, the guest had some guidelines laid out in etiquette books, but it also sometimes required a little sleuthing:

“Visits of ceremony, merging occasionally into those of friendship, but uniformly required after dining at a friend’s house. Professional men are not however, in general, expected to pay such visits, because their time is preoccupied; but they form almost the only exception. Visits of ceremony must be necessarily short. They should on no account be made before the hour, nor yet during the time of luncheon. Persons who intrude themselves at unwonted hours are never welcome; the lady of the house does not like to be disturbed when she is perhaps dining with her children; and the servants justly complain of being interrupted at the hour when they assemble for their noon-day meal. Ascertain, therefore, which you can readily do, what is the family hour for luncheon, and act accordingly.”

Decorum by S.L. Louis, (1881)

What always seems to be agreed upon is that visits should be very, very quick:

“Ceremonious visits should always be short, fifteen to twenty minutes being the outside limit, and a shorter time often sufficing, Even should the conversation become very animated, do not prolong your stay beyond this period. It is far better that your friends should regret your withdrawal than long for your absence. A lull in the conversation, a rising from her seat, or some pretext on the part of taking which should be made use of at once.”

Social Etiquette by Maud C. Cooke, (1899)

Formal attire was expected and there was an entire category of dresses specifically made for afternoon calls. Hat, gloves, fan and parasols, (depending on the fashion of the time) were all worn and were not removed during the visit. There was some leeway for gloves during cold weather as one or both might be removed when one drunk ones tea and heavy veils could be lifted if you were with a good friend.

Long before the advent of the internet, the practice of calling was dying out, as Amy Vanderbilt noted…

“In Victorian days and up until the First World War the making of calls was a highly stylized business. The duty fell of the women of the household, who left their husbands; cards with their own. However on certain occasions, such as calls of condolences, of congratulations, or calls on the sick, men often made their appearance and left their cards in person, too, as they still properly may. Today with increased apartment living, virtually servantless households, and fewer women who live a purely social life, formal calls involving the leaving of cards on various members of the household and their house guests are growing fewer and fewer. In some quiet communities and in some wealthy and conservative older circles in New York formal cakes are still expected and do take place. But few and far between are the hostesses who by engraving a day of the week on the lower left of their cards let it be known they are “at home” to callers of a certain day.”

Amy Vanderbuilt’s Complete Book of Etiquette, 1957

Unless some sort of electronic apocalypse happens, I don’t see the ritual of calling coming back anytime soon. To be honest, I find this a little sad. I think it would be lovely to have a day that people could drop by to say hello, maybe run into an old friend or make a new one. Alas, it will not be.

I do hope you’ll invite me to visit once the 2020 end times are over. Let’s all visit as soon as we can. Much love, Cheri